By Rasamandala Das

Click here to download this article as pdf

In my last article,1 I predicted that ISKCON was entering a new and dynamic “third phase” of development, typified by a systematic approach towards training and education. Since then, several educational initiatives2 have progressed significantly. Nevertheless, in some cases, they have aroused concern from devotees for drawing on philosophies and practices 3 from beyond the tradition. In this essay, I’d like to explore how one such discipline, quite conventional in secular education, relates to its Vedic4 counterpart. I will propose that the two are not inconsistent. 5 On the contrary, I have drawn up an amalgamation of both, advocating that this new model serves as a basis for further research and development. Furthermore, I will use it as a measuring stick, to subsequently examine where ISKCON stands within its educational evolution. In so doing, I will present and support evidence to suggest that formal education is perhaps the most important element in ISKCON’s continuing social and theological development. I will conclude with making specific proposals for implementation.

In this study I will be largely drawing on my own experience, thus focusing primarily on adult education (though many conclusions will be relevant to gurukula6). In part, I am also responding to the essay Sefton Davies presented in the last edition of the Journal 7, and would welcome his comments and, indeed, those of other experts, devotees and non-devotees alike.

Knowledge, Skills and Values

Modern educationalists divide all that we learn into three broad categories, each with its attendant verb8 (as shown in the table below)

| Knowledge | what the student will know |

| Skills | what the student will be able to do |

| Values and Attitudes | how the student will be. |

Comprehension of these three items is essential when establishing the aims and objectives for any learning process (and aims and objectives invariably fall within these three divisions).

Furthermore, various learning methods are deemed more or less appropriate for each of these categories. Sefton Davies highlighted this in his last article 9, adequately explaining the benefits of “experiential learning” for teaching “skills”. He also mentions the inordinate emphasis which ISKCON places on knowledge acquisition and on the corresponding modes of teaching.

I have been using this “knowledge, skills & values model” for over three years, particularly in training other devotees as teachers and facilitators. I am personally convinced of its merit and have received only positive feedback from students. Nevertheless, for some time I was feeling uneasy, on two accounts.

Firstly, I had little conclusive scriptural endorsement for my teaching practices (which contributed to some devotees questioning their validity 10). Secondly, as I grappled for a firm understanding of my subject, three important questions remained unanswered:

- How do the three objectives rank chronologically? Is each predominant at some specific stage within the learning process? 11

- Does there exist a hierarchy of importance amongst the three, and if so, what is it?

- Where does the concept of “understanding” fit in? 12

Naturally, my colleagues and I had our own ideas, largely distilled from personal experience. In response to question 1 (above), we surmised that knowledge-transmission was typically predominant at the start of any scheme of learning. Nevertheless, we weren’t sure about the respective processional positions of “skills” and “values”. “Do they develop concurrently”, we asked, “or one generally before the other?”

Our response to the second question (above) was less equivocal. We firmly concluded that (within ISKCON at least) the category of “values” achieves top priority. We identified shastric examples to support our case – that the ultimate goal of education is to transform the nature of one’s being (or, in other words, to become Krishna conscious). This involves becoming humble, tolerant, compassionate – and, indeed, developing all the twenty-six qualities of a Vaishnava.13 A subsequent study of the first of “The Seven Purposes of ISKCON” 14 appeared to endorse the same conclusion 15 – that the whole thrust of ISKCON’s education is to effect a change in values.

Vedic Evidence

Despite these findings, I still felt we were far from a definitive and clearly-codified understanding of the educational process. Then (as destiny would have it) my god-brother, Bhakti Vidhya Purna Swami 16, kindly gave me a copy of notes 17 including pertinent scriptural references. I later explored these verses, focusing on how they might clarify our comprehension and definition of education in terms of knowledge, skills and values.

According to the Brihadaranyaka Upanisad (2.4.5), there are three broad stages to any learning process. They are:

- Sravana – hearing knowledge from the teacher

- Manana – gaining an intellectual understanding by reflecting on what is learned.

- Nidhidhyasana – realisation and application in one’s life.

From this verse I ascertained the following:

- knowledge transmission is indeed the preliminary stage of education (as we had suspected)

- ‘understanding’ is part of a subsequent, second stage.

- skills and values appear to be relevant later on (expressed as “application in one’s life” 18 and “realisation” 19).

Nevertheless, it was still not clear as to whether “stage two” (manana or theoretical understanding) represents a progression from stage one in terms of skills or values (or a combination of the two). In other words, does “knowledge” transform into “understanding” through the acquisition of skills, the development of appropriate values, or through the parallel evolution of both)?

I then came across a verse from Sriharsa .20 In his Sanskrit poetical work, the Nasadam 21, he delineates the following four stages of learning:

- Adhiti – to learn a subject thoroughly

- Bodha – to gain insight and proficiency in one’s learning

- Acarana – realising the purpose of, and living according to, our learning

- Pracarana – giving this knowledge to others

I assumed 22 that the first three stages included in this second sloka correspond to those listed in the first. The fourth stage, I will not discuss here (though it is obviously important and clearly distinguished from the other three)

From this verse, it became clear that the “second stage”, according to our developing “Vedic model”, not only encompasses an intellectual grasp of the subject, but a concomitant practical application of such understanding. I deduced that skills are learnt primarily at this second stage. Nevertheless, there is not full-realisation, nor have those skills become “second-nature”. This only occurs in the final, perfectional stage, where the knowledge, understanding and skills become internalised, or part of oneself. In other words, the student or apprentice becomes an engineer, a carpenter or a teacher (or in Krishna conscious terms, a pure devotee). He lives and breathes his subject, easily and effortlessly. It is the platform of spontaneity.23

Towards an Integrated Philosophy of Education

I subsequently concluded that this second stage of our Vedic model corresponds to “skills”, and the third to “values” (which represents the ultimate goal of learning.) In attempting to clearly distinguish between these two stages, I have postulated that each of their outcomes correspond to “conscious competence” and “unconscious competence” respectively 24 (an idea I then extended to relate our Vedic paradigm to this entire “four-step model”.)

Despite these suppositions, I felt this model to be incomplete. I suspected that, to some degree the three strands evolve in parallel throughout the whole process and become perfectly integrated during the third and final stage. I suggest that this is indeed true, but that the explicit emphasis of teaching changes at each stage. For example, knowledge progresses from mere “theoretical knowledge” (conspicuous at the beginning of learning), through “intellectual

understanding”, to culminate in “full-realisation”. Skills, latent in the beginning, form the focus of the second stage, and subsequently become fully internalised. It is here, a this final stage, that values take prominence, in the sense that knowledge and actions must be integrated into one’s life, becoming perfectly congruent with self and desire 25. It is the stage of becoming exemplary in thought, word and deed , as expressed in the term “acarana”.

For each strand, I have also identified, from the Bhagavad Gita, 26 three key characteristics required of the student, namely inquiry, submission and service .27 The entire model, shown on page XX, may provide ISKCON with a foundation for formulating a comprehensive philosophy of education, firmly rooted in the tradition and explicitly endorsed by scripture.

Further Research

There remains ample scope for further research., particularly into shastra, and I’ll here indicate a few likely areas. The three terms “knowledge”, “skills” and “values” still beg precise definition.28 The Bhagavad Gita, particularly chapter eighteen, 29yields further information.

According to our initial definition, “values” relates to “being”. This alludes to the self, which the Gita describes as the “knower” and “the doer”30. Values therefore refers to the intrinsic nature of the self (however one conceives of it), suggesting that this final stage of learning in identical with “the unfolding of the self “, or realisation of one’s “sva-dharma”31. It also suggests “desire”, since “what we value” is largely determined by the nature of our desires. In fact, according to the Gita, our whole destiny rests upon the nature of our desire and the very purpose of the spiritual path is to purify the heart of its materialistic propensities.32

The other two stands (knowledge and action), cannot exist independent of the self. (The converse is also true – that there is no existence of the self devoid of consciousness e activity 33) There appears to be an ongoing reciprocation between the two, which, I conclude, the experiential learning cycle 34demonstrates. There are numerous other quotes in the Gita and other Vedic texts 35which demonstrate the various relationships between our three strands.

I would therefore conclude that the analysis of education in terms of knowledge, skills and values is largely or wholly consistent with the Vedic model. I would further suggest that the Vedic version positively embellishes our understanding of education and its ultimate purpose. Bhakti Vidhya Purna Swami his written, “The thrust of education, therefore, must be to develop character and philosophical realisation; external knowledge and expertise are in a supportiverole”. 36

Part Two

In this second part, I intend to continue our exploration of contemporary educational procedure (including that considered more progressive), to examine how it may be applicable within ISKCON and, indeed, where it may be inappropriate. We will particularly focus on aims and objectives, and how they are achieved through a variety of teaching methods. Our conclusions

will again be useful in helping us analyse where ISKCON currently stands and in formulating proposals for educational development.

Aims and Objectives

An essential feature in the design of any learning programme is the clear definition of aims, categorised according to knowledge, skills and values. In my last article, I identified the pressing need to establish the concept of “graduation from the training ashrams”, specifically to enable the Society to “keep the end in mind” and to formulate clear aims in terms of its most important resource – its committed members. Without such formal education, there is no question of a deliberate and pro-active approach towards developing the various categories of ISKCON’s membership.

Srila Prabhupada confirms the importance of setting aims:

Srila Prabhupada: “…If you have no goal…There is example: “Man without any aim is ship without any rudder.” So suppose if…aeroplane is going with an aim to land in some country, but if he goes on simply without any aim, then there will be disaster So without aim, what is the use of practice?”

Prthu Putra: “He says he like the practice without goal.. ”

Srila Prabhupada: “That is foolishness. Without goal, practising something, it is foolishness.”

Srila Prabhupada Conversation, 13 June 1974.

We will examine later how the Society’s trainers are often unclear as to what constitutes their specific goals (although, quite ironically, often claiming that they are obvious and hence require no explicit delineation). We will return to this in Part Three. Suffice it is here to mention that there are two further stages in planning, developed in response to the questions included below:

- Aims – what do you, or your organisation, want to achieve taking into account the learning needs of the students?

- Objectives – what will the students be able to do at the end of your lesson or course which will demonstrate that you are meeting your aims?

- Assessment- how you will assess whether students are meeting their objectives (and hence whether you are all successful in meeting your aims.)

In planning, these three steps are essential and must be formulated sequentially. The tendency37 is to neglect them and jump ahead to immediately consider content. The reader may reflect on his or her own preparation of a class or lecture. Most of us will:

1) identify topics related to our main subject.

and 2) determine what exciting learning experiences could be included

If we are more experienced, we may also initially pinpoint a theme which we intend to follow throughout. Even so, this approach remains relatively ineffective. Educational experts term it “content-driven”. Teachers remain more concerned for “what” is taught than for “why” they are teaching in the first place. It is no less essential to have clearly focused aims when teaching

than in life itself. Without such, we will undoubtedly run into difficulties, particularly an inordinate leaning towards knowledge-transmission, and a commensurate marginalisation of skills and values 38. One of Sefton’s principal criticisms of ISKCON is that it’s educational processes focus on knowledge acquisition, as demonstrated by it’d predominant modes of teaching.

Let’s now examine some of these different methods and the possible rational behind them.

Teaching Methods and Styles

One of my aims in training has been to broaden devotees understanding of what constitute effective teaching 39.Most devotees have warmly welcomed these changes as reflecting a positive shift in values. Nevertheless (and quite understandably), they have not been without their critics. A parallel debate exists in the secular world between the advocates of “traditional” and “progressive” practices.

Sefton highlights this dynamic, contrasting education which is primarily concerned with “putting in” 40 with that which is largely “drawing out 41 He writes, “The extreme case of putting in is that of indoctrination, where an educator wishes to implant a fixed set of ideas and to exclude the possibility of contrary ideas being considered and accepted.”

Here he implicitly addresses two issues:

- the correlation between any society’s education and its style of government (suggesting that the particular mode of education may well reflect the prevailing ethos within its leadership.)

- the dialectic between the needs for (a) authority (represented by the Society) and (b) exercise of free-will (as expressed through the individual).

These, I propose, are two essential points for ISKCON to consider and themes we will pick up later in the article.

Sefton’s statement implies that an educational system favouring “putting-in” may be rooted in the desire to preserve and perpetuate a fixed set of ideas. Ideological groups, including ISKCON, fall within this category. But can they not adopt progressive styles of education?

Sefton has personally shared with me his conviction that it is (almost) impossible. In other words, any organisation with a fixed doctrine is obliged to be prescriptive. I suspect that his ideas are not without foundation. We may reasonably ask, “How can ISKCON teachers afford to draw answers from students since some responses will inevitably be at variance with Gaudiya Vaishnava theology?”.

In answering this question, I will relate an experience from my school days. Our physics teacher, Mr. Jones, would regularly ask us to conduct laboratory experiments. I recall one in particular, involving weights, scales, thread, water, balances and so on. Our task was to measure the effective weights of different objects immersed in water. We were then to plot a graph of two sets of readings and then estimate a corresponding formula On this day, I remember, I couldn’t be bothered – and I was a theorist anyway and already knew the correct answer. So, I worked backwards, constructing the graph from the formula, and then dotting co-ordinates along its length (not right on the line, lest Mr. Jones became suspicious of my unerringaccuracy.) It was then easy-as-pie to fill in the corresponding “readings” and to gloat over my early finish.

I was naturally convinced of the accuracy of my “experiment”, and no less so than if I’d actually performed it! Nor was the teacher anticipating a conclusion from any student far different from the one he expected. Why then did he have sufficient faith in his students (providing, of course, that they correctly followed the standard experimental procedure)? The answer will be clear to my reader (and please excuse me if I state the obvious): fundamental laws of nature cannot be contravened. For this reason, events which such principles govern are entirely predictable.

According to Vaishnava theology, such universal laws apply just as much to subtle phenomena as to gross, to living beings as much as to dead matter.

I will conclude that student-based learning is appropriate when we are dealing with axiomatic or universal principles, considering the subject to be science rather than mere faith or belief.

Conversely, such methods may not be suitable where the predominant beliefs, values and practices of a society or individual are incongruent with reality; such ignorance can hardly flourish in an atmosphere of open and honest inquiry but requires a healthy dose of unquestioning compliance (as is evident in the scientific world, as well as the overtly

“religious”)42. We may therefore rightly suspect the integrity of any organisation or society which restricts, explicitly or implicitly, the right of the individual to openly inquire.

Another argument supporting a student-centred approach concerns the whereabouts of knowledge, which the Vedas consider to be locked within the heart. The whole process of teaching is to evoke that inherent wisdom. The whole process of “drawing out” is consistent with this understanding and, if performed properly, will yield accurate results.

My personal experience of teaching confirms this. If devotees observe their spiritual practices, then the facilitator, through nurturing honesty, introspection and self-expression, can almost always evoke the “right” answers from students themselves. Naturally, there are risks involved – true for anyone who dares teach in a more dynamic, student-centred way – which naturally puts an onus on the facilitator to truly understand and realise the subject 43 or to admit his inadequacies. In either case, it calls for depth of character (what to speak of a willingness to take risks!). Again, this suggests that teaching methods reflect not only the managerial or organisational ethos (as previously mentioned), but the values held by teachers themselves 44.

This may further indicate that in borrowing educational methods from outside ISKCON, devotees must be careful not to adopt values which are inconsistent with their tradition.45

An Analysis of Experiential Learning

Certainly, my own support for progressive educational practice is not without qualification. For example, I often teach according to the “experiential learning cycle46.

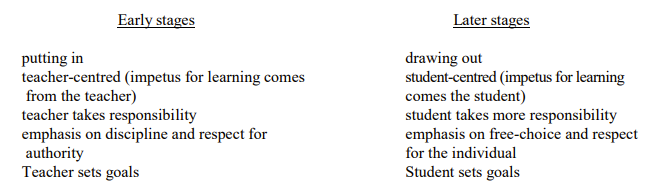

From a Krishna conscious perspective, however, this process is to abstract not so much ideas as realisations. Therefore, to differentiate between factual and erroneous conclusions, student perceptions 47 must constantly be tested against shastra.48 This requires, in most cases, that students have some preliminary scriptural knowledge. In addition, the process of drawing out answers is dependent on students’ adequate experience of the subject. These two reasons together imply that “putting in” is more appropriate towards the beginning of any learning process,49 whereas drawing-out 50 is more suitable later on. Similarly, there are other features of effective learning which predominate in the earlier and later stages respectively. These are shown below:

These two sets of criteria closely correspond to the traditional and progressive models. I propose that each is relevant, and each essential, at its respective stage. The progressive model may not be appropriate without the student having passed through the earlier stage. Similarly, to maintain highly didactic methods for mature students may prove equally counterproductive.

The criteria listed above may again help us analyse ISKCON in its provision of educational opportunities.

The Importance of Principles

Let’s return to our examination of experiential learning. We have identified the need to speak of -“realisations” rather than “ideas”. I would further postulate that the whole purpose of experiential learning is not to abstract simply policies or guidelines, but primarily principles. Why do I emphasise this (and I do so repeatedly!). For this reason: unless a social group understands the foundational principles behind is specific raison-d’être it will not be able to effectively respond to changing circumstances, nor preserve its tradition Specifically it must discern between context-relevant instructions (or temporary policies) and unchanging, axiomatic truths. Otherwise, it will commit one of two blunders;

either (1) taking account of, and reacting to, changing circumstances and public opinion, but losing grip on its core beliefs, values, mission etc.

or (2) sticking rigidly to externals, and to doctrine, often in the name of preventing mission-shift, but losing the real essence of that which needs to be preserved and perpetuated

It is essential that ISKCON preserves its legacy, and here, I suggest, training and education will play a key role.

A further advantage of a principle-based approach (over one which simply defines practice and procedure) is it’s legitimate accommodation of diversity. It is flexible, but not capricious; liberal, but not promiscuous; doctrinal but not doctrinaire. It maintains and communicates clear standards by which to gauge a wide variety of practices. It is not the culture of rigid compliance and conformity, but values the individuality and initiative of all the Society’s members (though within the bounds of the mission which defines their membership). Additionally, a principle- based approach will enable the mission to synthesise its conservative and radical features and avoid fragmentation into various opposing camps. Principles form the bedrock of continuity.

Such principles are found within Srila Prabhupada’s books53.

The Role of Scripture

One may, however, question the need to use experiential learning at all. The Vedas are considered infallible. Why not just accept them – end of story? One danger to such a prescriptive approach 54 is that students fail to question not only the validity of scripture 55, but also their understanding of such sacred injunctions. Consequently, they may pretend to understand, or possess appropriate levels of conviction. Lack of opportunity to clear away doubts subsequently impedes progress. 56 This naturally involves a degree of self-deception.

Leaders and teachers in such societies may be more concerned with belief and faith allegiance than an open exploration of truth. There may also be preference for “yes-men”, an “us and them” mind-set and reliance on hype, slogans, and peer-pressure to support practices which are often carefully tended as sacred cows.

Therefore, we may conclude that an effective educational system promotes understanding and realisation – an internalisation of that knowledge derived from appropriate authority.

The Basis Of Commitment

Our discussion raises another pertinent question; “Is commitment based on a full exploration of facts or a suspension of the critical faculties?”57 In the eighteenth chapter of the Bhagavad Gita, Lord Krishna apparently supports the former i.e the path of the well-informed decision. After instructing Arjuna for the best part of an hour, the Lord tells him, “Thus I have explained to you knowledge more confidential. Deliberate on this fully, and then do what you wish to do.” (B.G. 18.63) Srila Prabhupada further explains in his purport, “Surrender to the Supreme Personality of Godhead is in the best interest of the living entities. It is not for the interest of the Supreme. Before surrendering, one is free to deliberate on this subject as far as the intelligence goes; that is the best way to accept the instructions of the Supreme Personality of Godhead. 58

This text not only advocates the need for teaching methods which stimulate real understanding, but the benefits of enrolment policies which acknowledge the free will and individuality of the student 59 (as we touched upon earlier). Assessment should precede each stage of commitment, so that the candidate can take full responsibility for his or her decision. Contrary procedure may lead to premature commitment, which not only causes later retractions, but may also result in bitterness towards the organisation which didn’t meet unrealistic expectations. In other words, a society such as ISKCON has a responsibility to clearly delineate to the candidate their future prospects.

Simultaneously, any enrolment policy requires the clear understanding of the specific purposes of that programme and then to establish quantifiable enrolment criteria 60. What is also clear is that the type of person who, say, joins the ashram, will greatly affect the society’ organisational culture.

It is therefore crucial to test ISKCON’s policies and procedures to see if they match these criteria. What is imperative to recognise is the need to establish aims for the different training programmes in the Society. This in turn determines one’s enrolment policies. Unfortunately, as we’ll examine later, there are very few with such clearly defined aims. In fact, until recently there have hardly been any formalised educational programmes within the Society. In other words, the Society and its leaders have as yet not recognised the benefits, which leads to an important question: why not?

Leadership and Values

Whatever the answer to this question, it is clear that education does not take place within a vacuum. It needs not just the endorsement but the active and heartfelt support of the entire Society, and particularly its leaders.

Values are not determined by what is simply written or spoken (for example, in ISKCON’s case, from the Vyasasana). They are largely determined by social interactions, particularly through the behaviour that is either rewarded or punished. Therefore, the prevalent leadership ethos will largely determine the nature of any society’s education system. It is also the duty of leaders to ensure through appropriate evaluation that their organisation is on course for meeting its aims.

In this respect, there seems ro be a clear parallel between the managerial and educational processes. In many professional organisations, training is simply a matter of expediency in meeting its financial goals. It is clear that ISKCON’s very aims are educational as revealed through the first of its Seven Purposes:

“To systematically propagate spiritual knowledge to society at large and to educate all people in the techniques of spiritual life in order to check the imbalance of values in life and to achieve real unity and peace in the world”. (highlights are mine)

For this reason, the managerial function must serve the educational processes, and not the other way round. The following analysis of ISKCON and subsequent proposals are especially

intended for the consideration of the Society’s leaders.

Part 3

So far we have examined learning in terms of (1) knowledge, skills and values and (2) aims and objectives. We have also briefly explored various teaching methods and identified the need for education to be principled-based and grounded in scripture. In so doing, we have identified criteria to define effective education, and its corresponding systems and structures. Let us now use these guidelines to ascertain how far and how effectively ISKCON has progressed in it’s provision of education opportunity.

ISKCON, as an emerging world religion, is in its infancy. A promising future is not without teething pains. Systematic training and education will positively address many of the painful challenges which the Society faces. This naturally involves identifying its shortcomings, not in a mood of criticism but as an attempt to realistically and constructively move forward. There are many indications that the Movement is positively evolving as it enters “Phase Three” of its development 61Many of the observations listed here refer to the previous two phases as well as, to some degree, the present situation:

The following analysis is divided into four sections 62 as follows:

- Knowledge

- Skills

- Values

- Formal education (beginning with establishing aims)

Knowledge

(1) There is an over-emphasis on knowledge-acquisition

Here I’d like to share a personal anecdote. Four years ago, at a public function in Bristol, I was chatting to one lady, a member of our “congregation”. She had recently attended one of my week-end courses on teacher training. I was encouraging her to “give it a shot” at leading a local class. She, however, was hesitant. Finally she revealed that she felt herself unqualified. “I don’t know enough slokas!”, she admitted. I was astounded! Here was a middle-aged woman, a

certified counsellor, who’d successfully raised a family and demonstrated maturity in her personal and professional dealings. I was simultaneously bewildered and enlightened! I was convinced, (and I told her) that the values prevalent in our temples were spilling over into the congregation . She had the necessary skills, and the appropriate attitude, and yet considered the number of verses she could recite the primary criteria for representing the Society.

It would be interesting, if not revealing, to ask members of ISKCON’s important publics (e.g. academics, the media and faith leaders) what they expect of our members. We could also ask ourselves what our own tradition says about the respective priorities afforded to knowledge, skills and values?

(2) educational methods are almost entirely teacher-centred

Within ISKCON temples, lecturing remains the predominant mode of teaching. Devotees are often reluctant to use other means, often doubting there authenticity. Some even consider them “non-traditional”, or even heretical, citing our standard process of “descending knowledge”.

Amongst some progressive non-devotee educators, lecturing is considered suitable for little more than knowledge-transmission. Conversely, it holds within Vaishnavism a place of honour and cannot possibly be equated with mere information-transfer. On this point, there seems to be a clear rift between non-devotee experts and the tradition itself. I have been contemplating this for some time, trying if possible to resolve the issue (and I have some thoughts on this)63 For such formal temple situations, I am reluctant to suggest that devotees use radically methods.

Nevertheless, there is precedence for using such techniques. In Part One we examined how realisation constitutes one of the ultimate goals of the educational process. It is interesting to examine how Srila Prabhupada defines the word:

“Personal realisation does not mean that one should, out of vanity, attempt to show one’s own learning by trying to surpass the previous acharyas. He must have full confidence in the previous acharyas, and at the same time he must realise the subject matter so nicely that he can present the matter for the particular circumstances in a suitable manner. The original purpose of the text must be maintained. No obscure meaning should be screwed out of it, yet it should be presented in an interesting manner for the understanding of the audience. This is called realisation.”

This quote endorses the principle of adjusting one’s presentation to suit the audience, and may indeed support the whole concept of progressive educational technique, which, I suggest, at least should be considered outside of the formal lecture context.

(3) The Society has little promotional material beyond canonical literature

Just a few days ago, before visiting my father, he asked me to bring for a friend some preliminary literature on Krishna Consciousness. I naturally agreed, but subsequently felt embarrassed with what I couldn’t find. No details on the devotees themselves, nor their personal stories; very little on the Society’s cultural heritage; next-to-nothing on the opportunities it offers the public; and little with any pictures! But tons of text and tons of doctrine (which, for most people, is presented quite unsuitably)

ISKCON members rightly take pride in their sophisticated theology. Many now perceive that this is insufficient, and that they need to practically demonstrate their teachings, and to “walk their talk”. For a society of our size and prominence, the lack of suitable literature reveals, again, an inordinate emphasis on knowledge alone, or on the importance members give to mere belief.

Skills

(4) Little importance is attached to skills training

Lack of skills training is evident in various ways. We often observe capable devotees performing relatively low-level tasks, when compared to the secular world with its effective training systems What is becoming apparent, gradually, is the huge cost of not training members and of the gross inefficiency in repeatedly re-inventing the wheel. Inadequate skills also become conspicuous in areas which impinge on public perception, such as our reception and telephone services. The whole issue of credibility can be effectively measured simply in terms of skills and values (which are often reflected through conduct and behaviour).

Another key issue is the lack of vocational training for the vast majority of residential devotees who will eventually marry

(5) There is little or no service assessment and insufficient accountability

Within ISKCON, sincerity is often considered the sole criteria for maintaining a role or position Any attempt to assess may be construed as an affront to one’s personal integrity. In leadership circles, the sporadic coups which tear down temple presidents may be attributed to a lack of formalised performance evaluation. In the 80’s, initiating gurus were automatically jet-set executives, on account of their spiritual standing, and expected to be knowledgeable in all subjects, whatever their factual experience.64

A corollary of these phenomena has been the reluctance of temple devotees to engage the skills of congregational experts whose spiritual practices failed to meet temple standards.

In conclusion, material propensities and spiritual qualifications have been totally confused

Values

(6) There is a lack of congruence between devotees theoretical knowledge and the values they demonstrate

The early Eighties saw devotees recognising the dichotomy between doctrinal theology and spiritual practice. Shortcomings in values were reflected through poor, and often shocking, personal conduct and a striking increase in social anomalies.

I have listed below some of the values which the Society seems to have (unconsciously) nurtured in its members and are inconsistent with shastra:

(a) short-term results have been rewarded more highly than long-term commitment.

Scripture advocates the relative benefits of sreyas (ultimate good) over preyas (immediate benefit). Despite his, new devotees who have contributed significantly towards fund-raising initiatives have often received far greater acclaim from leaders than older devotees who are no longer so financially productive. It is therefore questionable, from an educational perspective, whether the appreciation a member receives is commensurate with his or her factual spiritual advancement (as it should be). One noticeable result has been that leaders often cater more effectively to younger followers than those more mature.

(b) devotees have favoured “transcendence” in preference to “mundane morality”

In the early days devotees failed to appreciate the importance that basic morality plays in reaching transcendence. Self- realisation, or perception of the self separate from the mind and body, was considered to be quite different from character formation. These attitudes naturally mitigated the need for introspection and any deliberate values assessment.

- external renunciation has been valued far more than integrity and personal responsibility. The leaning towards artificial renunciation and consequent

irresponsibility is particularly evident when studying brahmacaris’ (often negative) attitudes towards marriage and the fair sex. The grihasta ashram has often, quite erroneously, been equated with materialistic household life. The consequences for brahmacaris changing ashrams have been, predictably, disastrous.

- the prevalence of the “welfare mentality”. Devotees have often expected the Society to provide far more of their needs than it is able and eventually become disappointed 65 This raises the question of establishing mutual expectations and, furthermore, the type of people acceptable for residential training66

- unquestioning allegiance has been given preference to thoughtful commitment Faith based on suspension of the critical faculties certainly results in a quick commitment, but not usually a lasting one.

- spirituality is measured largely on the basis of external practices, rather than inner development. Although strict adherence to sadhana is undeniably essential, there has been very little open dialogue about personal issues and what is really going on within the devotee’s heart.

(7) shastra has been misused to endorse erroneous practices and their attendant values

ISKCON has its share of “buzz” and “snarl” words, which often embody unquestionable truths and values. For example, when a devotee is insensitive he or she is invariably described as “impersonal”, with all its connotations. Other terms worthy of exploration include “surrender”, “humble”, “independent” and “motivated”. Although these terms are theologically significant, they may have been unconsciously misinterpreted for tendentious purposes, usually related to maintaining a high degree of hands-on control (e.g. to keep the work-force enthusiastic).

(8) Business (vaishya) values have been predominant

Inappropriate values lie at the heart of many of the Society’s challenges and may be the natural consequence of the emphasis by leaders on productivity, itself moulded by circumstantial economic pressures (rather than as the direct fault of management itself.) Those with brahminical tendencies (who tend to be independently resourceful) have not always felt appreciated nor found satisfying services. Many, after living in temples, have ultimately pursued careers away from the Society

(9) Discerning people have been reluctant to become closely involved

Temples filled with less-discerning residents have scared away the more intelligent 67. Many temple residents become highly dependent for their material needs and failed to win respect from the more intelligent and professional classes.

When questioned on subjects beyond their capacity, they often become defensive and attempt to maintain their own perceived superiority by borrowing strength from position, length of time in the Movement, etc. Traditionally the temple and its residents are expected to be exemplary and such training is reserved for men and women of he highest calibre.

Formal Education

(10) There is little formulation of people-centred goals

Members, according to their respective levels of commitment, constitute ISKCON’s most valuable asset and yet cars, books and property take priority. Material assets have been often been considered the means to secure followers, rather than vice-versa. This calls for a re- evaluation of the actual purposes of the Society..

(15) There is very little continuity and progression

Many congregational members complain that they have been listening to the “you are no this body” class for the last six and a half years. Similar concerns are expressed by temple residents. Both educational content and methodology lack continuity and progression Teaching methods and styles are more suitable to newer members. The rationale behind this stasis is that:

- hearing is purifying anyway

- repetition is necessary, because we tend to repeatedly forget and fall into illusion

This approach does not acknowledge and validate the intelligence of students, nor recognise the progress they will have inevitably made if educational procedures are sound.

(13) Few clearly delineated systems and structures for training

Of all temples world-wide, less than thirty per-cent have even an initial bhakta/bhaktin course, what to speak of more extensive programmes. Intelligent people plan for the future, but the Society doesn’t offer them clear and positive prospects. For many, Krishna Consciousness remains a distant dream rather than a goal towards which they are consistently and perceivably moving.

(16) No clear enrolment policies

In most temples, the criteria for who is eligible to join remains a mystery and has been highly subjective (and hence subject to gross inaccuracy). Unsuitable candidates have often been accepted to ensure that pots are washed.

(15) New devotees are considered manpower rather than student

Temple department heads have sometimes opposed moves to introduce systematic training, as it means an initial loss of manpower. Ironically, formal training and education is ultimately intended (amongst other things) to equip temples with highly qualified staff.

What is clear is that the Society has not considered education a priority. Fortunately, opinions are shifting at the top and there are signs that ISKCON is indeed entering a new phase, in which we will see rapid strides in education as we enter the new millennium.

Proposals

The following proposals will be of particular interest to ISKCON devotees, especially leaders, managers and educators:

1. We clearly establish the vision, identity and function of all ISKCON temples, with specific emphasis on their primary role as educational institutes

2 (a) We identify the different publics who have educational needs. I have isolated four major categories namely :

- leaders and managers

- residential devotees (i.e. students)

- congregational members

- common-interest groups 68

- We establish the specific purposes of training and education for each of these publics

- For each group we establish paths of involvement, with aims and objectives for each stage of training in terms of knowledge, skills & understanding, and values

- each discipline within the Society establishes an educational team and subsequently,

(and largely from Srila Prabhupada’s books) the principles upon which it’s development is based, and upon these evaluates its training policies and practices

- We establish for all training courses corresponding enrolment policies and thereafter scheduled periods of commitment and assessment

- We publish appropriate advertising material which clearly differentiate between;

- our theology

- our understanding and experience of Krishna consciousness

- the opportunities which ISKCON offers to individuals for interaction with the Society

- Members who enter the Society for residential training do so with clear understanding of their future prospects, and on a contractual basis with defined rights and responsibilities.

- All teachers and trainers will be trained and accredited, according to international standards

(7). All managers should be trained, particularly to appreciate:

- the basic principles of leadership and management in regards to dividing society and training accordingly

- the value of supporting those with brahminical functions.

- the importance of continually improving the organisational culture of the Society, and ensuring that it’s representatives are aligned with its mission.

(8) Strong links should be forged between managers and educators to implement all the above and to ensure that the management procedures serve the educational purposes of the Society and that the predominant values within the Society are brahminical 69

Conclusions

I am convinced that our discussion points ultimately to varnashrama, which accommodates the common principle of service to Lord Krishna and, within that, the whole spectrum of values according to our respective positions within matter. Nevertheless, the predominant values within our society must be brahminical. Varnashrama, by which we can address all material and spiritual challenges, will principally come through the educational forum. If the managerial and educational leaders can co-operate to introduce systematic training and education based on the principles outlined in Srila Prabhupada’s books, then everything else will fall into place for the benefit of all.

Notes and References

1 Rasamandala Das (1995)

2 Particularly the work of the VTE (Vaishnava Training & Education), now centred in Oxford, England. Also the VIHE (Vaishnava Institute for Higher Education) currently constructing new facilities in Vrindavana, India and the Bhaktivedanta College of Education & Culture, based in South Africa, but more recently active in the US, India and Mauritius.

3 And hence possibly dubious values – which is, I suspect, the real concern of devotees questioning these methods

4 I use the term “Vedic” in the traditional sense to refer to any statement that is consistent with the conclusions of the Vedas or their supplementary texts

5 I suggest that there will almost certainly be some differences and that these should be carefully identified.

6 The Sanskrit term for “the place of the teacher”, by which I’m referring to the education of the Society’s children

7 Sefton Davies (1997)

8 These corresponding verbs will be useful when analysing the precise meanings of our three key terms

9 Sefton Davies (1997)

10 Quite rightly (although in some cases they openly denounced them without discussion or exploration). We did manage, quite early on, to identify many traditional examples of experiential learning. For further details the reader may consult VTE (1996).

11 Tentatively assuming that these stages will be applicable over both short and extended periods, and hence relevant to the single lesson, a prolonged course or an entire lifetime (and possibly more!)

12 It’s obviously important, and clearly more than mere “information transfer”. The reader may also note that I am assuming that our knowledge-skills-values model is comprehensive and all-embracing and can adequately define the whole learning process)

13 Delineated in the Caitanya Caritamrta, Madhya Lila 22.78-80 (Bhaktivedanta Swami, 1981)

14 Adopted at the Society’s incorporation at New York in 1966

15 In my previous article, I proposed that the brahmachari e brahmacharini ashrams, which comprise a major part of most ISKCON temples, be considered educational institutes, and that this has notable significance for education. On reading the Seven Purposes, I felt it clear that ISKCON itself is primarily an educational institute (though, I’ll hasten to add, not in the purely academic sense). This has already been thoroughly explained by Naveen Krishna (1997), who explored all seven purposes in this context. We will here simple explore the first, as follows:

“To systematically propagate spiritual knowledge to society at large and to educate all people in the techniques of spiritual life in order to check the imbalance of values in life and to achieve real unity and peace in the world”. (italics are mine)

My observations were as follows:

- Our three ‘key words’ are contained herein (“skills” being replaced with “techniques”)

- Srila Prabhupada wishes our approach to be systematic (in other words, “formal education”)

- There is a tangible link between society’s problems and any imbalance in values (this is relevant in that it supports the proposal that systematic training and education is one of the most important ways of constructively addressing ISKCON’s internal, sociological issues)

- That the ultimate purpose of education is to transform people’s values (i.e. what we value, which is so clearly connected to how we perceive the world). Whilst developing educational programmes in ISKCON, many devotees considered that this was far more important for devotees (or religious people in general) than for others. Some, therefore, preferred the term “character formation” in preference to “values and attitudes”. It is also clear that the ultimate purpose of Vaisnava education is self- realisation. This has raised the issue (though I won’t directly address it here) of whether or not “character formation” is synonymous with self-realisation, or superfluous to it.

16 A prominent sannyasi disciple of Srila Prabhupada and Principal of the Sri Rupanuga Paramarthik Vidyapitha , Gurukula in Mayapur, India

17 Untitled and unpublished

18 By “skills” I refer to anything which is identified with the verb “to do” – we could say “action” of any kind. It may not be so precise , but I use the term since it is used in the methodology we are currently studying.

19 I had assumed here that “realisation” correlates to “values”, since in the Vaishnava tradition it refers to the realisation of one’s inner identity, as the eternal servant of Krishna, and the development of all associated qualities, as supported by Srimad Bhagavatam 5.18.12. [see Bhaktivedanta Swami (1972)]. Later I considered that it might more accurately be considered an extension of our “knowledge” strand (though, as I will mention later, there may be a synthesis of all three at this final stage. In other words, all three are inextricably inter-linked.

20 XXX

21 Describing the story of Maharaja Nala from the Mahabharata. This reference is from passage 1:4

22 This issue remains open for discussion and the author welcomes any feedback

23Furthermore, we may note that unless one develops appropriate values, one will not have the impetus to apply the skills one has previously learned. Let us clarify the entire process by examining the career of a carpenter.

During his preliminary training the apprentice hears about the different types of wood, the tools he can use, the various kinds of joints, the range of adhesives, etc.. Subsequently, he gets an idea of “the big picture”, understanding how these various branches of knowledge inter-relate and consequently how they can be applied (in, for example, constructing a table) and learns the corresponding skills. During the later years, through continued practice, experience and service to his mentor, the knowledge and skills are internalised, until one finally becomes a master carpenter

24 Some experts imply that “values” objectives generally come before “skills”, though somewhat indirectly since they use the term “desire” instead of “values”. We have analysed values in terms of both desire and innate characteristics. The variance with our definitions may account for the differences, but it could also represent fundamentally contradictory opinions, possibly worthy of further research. In this connection it may be relevant to point out that according to the Vedic tradition, “love” (a possible objective of education) is a active verb rather than a passive feeling i.e. the act of service gives rise to the feeling, rather than vice-versa, which is the general Western concept of (romantic) love.

25 According to tradition, and particularly the system of varnasrama-dharma, the student must have from the very beginning the appropriate attitude and aptitude. This indicates that these are “drawn out” rather than “put in”. The author’s own experience is that of the two, attitude is most important. A student with no skills, but apposite attitudes, is far easier to teach than a student endowed with technique alone.

26 Chapter 4, Verse 34

27 Subsequently, I proposed that there is no knowledge without inquiry, no livelihood (or useful activity) without service, and no question of character without submission. The last statement is substantiated by Srila Prabhupada (1973) in the purport to text 13.12 of the Bhagavad Gita: “the beginning of knowledge, therefore, is amanitva,

humility”. (Lord Krishna uses the word “knowledge” here to refer largely to what we would term “values” i.e. non- violence, tolerance, simplicity etc.)

28 The same debate exists in secular circles. In the UK “skills” tends to refer to physical activities, whereas on the Continent it is a broader definition, encompassing more subtle abilities

29 Verses 13 – 45 in particular.

30 See verse 18

31 Literally “one’s constitutional duties”. Dharma, as we’ve mentioned, can also be translated as “implicit nature”, again implying the necessary congruence between values and action.

32 See Bhaktivedanta Swami (1973) “In other words, the tree of this material world is only a reflection of the real tree of the spiritual world. This reflection of the spiritual world is situated on desire, just as a tree’s reflection is situated on water. Desire is the cause of things being situated in this material reflected light” (Bhagavad Gita 15.1, purport)

33 The notion of action being constitutionally inseparable from the self is consistent with Gaudiya Vaisnava theology, though clearly at loggerheads with the advaitic stance).Srila Prabhupada writes, ”As soon as we say “cultivation”, we must refer to activity. Without activity, consciousness alone cannot help us” (Bhaktivedanta Swami, 1985).

34 Ascribed to Honey and Mumford, who describe four stages; doing, reflecting, abstracting and modifying.

35 The reader may wish to consult Bhagavad Gita (9.2, 10.7). Also the verse “Atmavan manyate jagat” – one sees according to the nature of oneself [original source unknown, adapted from Rohininandana Das (1990)]. Srila Prabhupada also mentions how the four qualities (mercifulness, truthfulness, cleanliness and austerity) are destroyed by the four sinful activities (animal slaughter, gambling, illicit sex and intoxication).

36 Bhakti Vidhya Purna Swami (1997)

37 I expect this is equally true for devotees and non devotees alike

38 this is not to suggest that factual knowledge and its transmission is not important

39 Especially to introduce them to more interactive methods.

40 based on telling

41 based on asking

42 for example, the author has heard of devotee children being mocked in school for questioning Darwin’s theory of evolution.

43 i.e to have internalised it. The reader may also refer to Sriharsa’s four stages of education, where realisation is a prerequisite to teaching.

44 These values may also significantly influence the type of person attracted to such an educational process. A teacher who does not possess the liberality of a brahmana will have difficulty attracting those with such inclinations. The authors experience is that they tend to become defensive and to suppress a mood of open inquiry.

45 More progressive secular facilitators often propose a highly relativistic point of view (e.g. stating that “one man’s truth is as good as anybody else’s). This can make facilitation easier, but is obviously at odds with ISKCON’s theology.

46 which Sefton outlines in his ICJ article

47 Perceptions can be erroneous or misleading. The Sri Isopanisad (199x, ), offers the example of mistaking a rope for a snake

48 I have implied here that the experiential learning cycle is incomplete without testing what one abstracts against shastra. Additionally, scripture may also define the activities themselves (the “doing” stage) and the values which the learner needs to develop (see diagram XX). Note that here I an referring to our knowledge, skills and values model, with the dialectic between perception and active response revolving around the object of knowledge, the inner person or the soul. Without scripture, or a locus-standi, it may be that such a cycle can be a downward spiral, rather than an upward one.

49 at the stage of knowledge-acquisition

50 understanding, realisation, latent aptitudes etc.

51 For example, according to tradition, freedom of choice is a privilege awarded to one who has proven to be responsible, having “passed the test of the spiritual master”.

52 According to the Oxford dictionary, this word has a number of meanings. We use it in he sense of unchanging laws (e.g. the principle of gravity, or the principle of karma)

53 I would further suggest that experiential learning without such a bedrock is inclined to go in downward spirals i.e. the learner may become increasingly ignorant. The Bhagavatam hints at this in the phrase “sufficiently inexperienced by years”. In other words, an erroneous world- view may reinforce behaviour which evokes responses appearing to confirm the learners faulty mind-set.

54 particularly if devoid of validated opportunity to question

55 which may be fine at the appropriate stage

56 As the ditty goes, “A man convinced against his will, is of the same opinion still”.

57 After all, commitment suggests the closing of certain doors, and even the opportunity to consider entering them.

58 italics the author’s

59 or indeed of anyone making a “faith-commitment”

60 devotees often consider this opinion heretical, since Lord Caitanya’s movement is intended for all without discrimination. Whereas that remains true, it does not mean that all candidates are suitable for all involvement options (e.g. not every aspiring devotee is suitable for ashram life).

61 as I identified in my previous article

62 though naturally there will be much overlap between them

63

I have noted that the morning Bhagavatam class doesn’t take place in isolation. It’s one part of an entire process, which has other highly experiential components. Lectures are delivered most effectively at the end of the “morning programme.” The attendant spiritual practices, particularly the chanting of japa, enhance the consciousness, making the practitioner far more aware and receptive to hearing. During the lecture, an effective teacher will draw from life experience, speaking with direct realisation, which will powerfully transform the heart of the sincere listener. The

devotee then carries forward what is learned into the day’s service, meditating on the teacher’s words. My own perception of this process is that even the lecture itself can be highly experiential, with the potency o transform values.

64 placing them under considerable pressure to perform according to such unrealistic expectations

65 or, even worse, detractors

66 particularly in respect of their values. Some candidates may already possess desirable traits, such as honesty and cleanliness, whereas others are practically incorrigible even after training.

67 i.e. those with higher values

68 XX

69 this means that leadership and management is proactive rather than reactive, responding to situations rather than reacting (or ignoring). The basis of its response must involve realisation and application of the principles given by Srila Prabhupada. This will also involve organising and training the Society according to the principles of varnashrama